Other than the greatest wines from the early half of the 20th century, I’ve smelt nothing as complex as the finest oud. Great wine expresses itself through the medium of fruit; oud expresses itself through the medium of wood.

Like wine, ouds vary enormously in price. None are inexpensive and some are extraordinarily so—I’ve experienced ouds ranging from $30 to $500 a milliliter. The greatest leave one in a daze, almost a trance.

The wild trees (less-expensive ouds are made from farmed trees) are rare. They must be at least 40-years old and attacked by a fungus that turns the wood black. They are found in increasingly remote areas in India, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, and Borneo, only reached after days of hacking through the jungle with machetes.

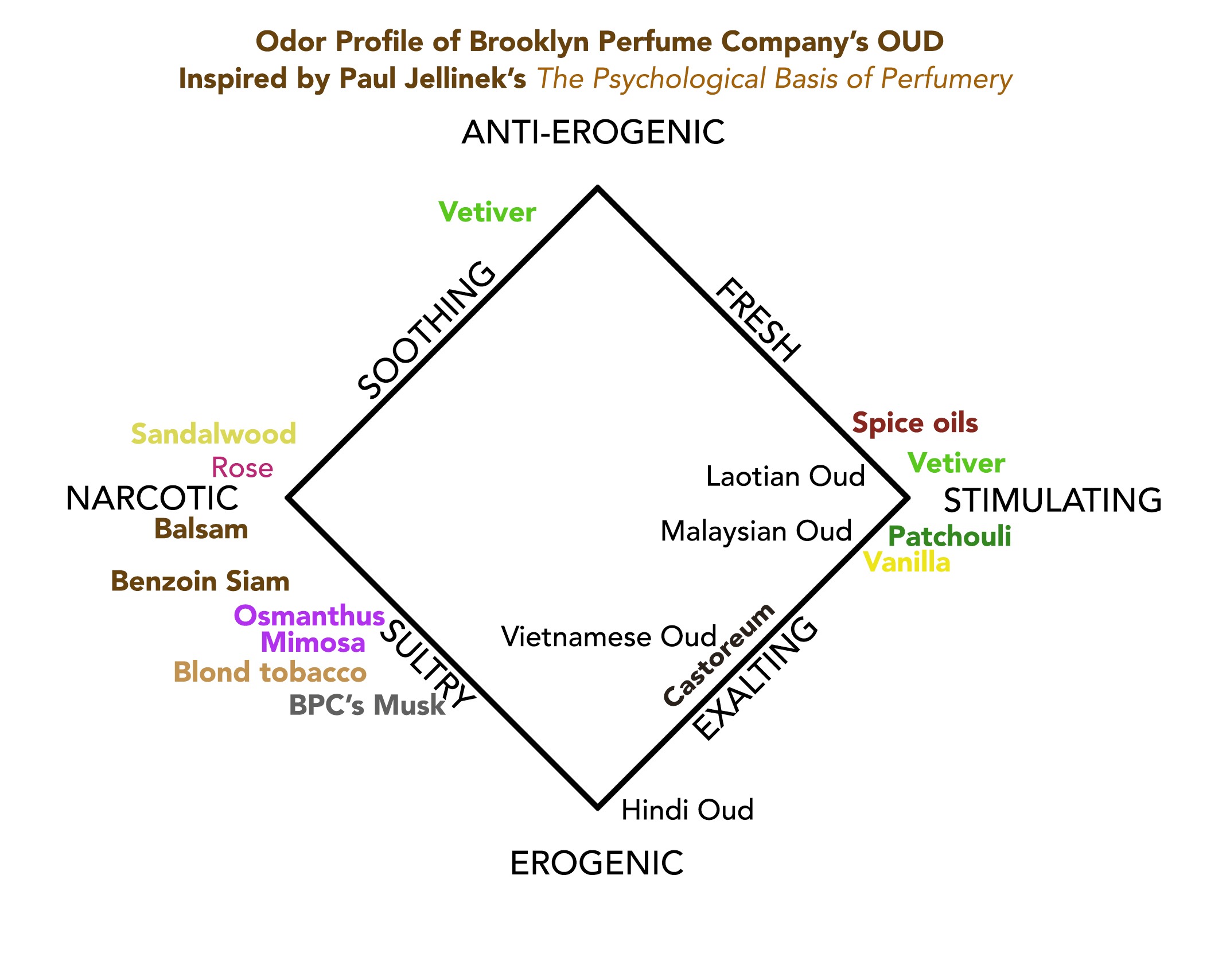

When looked at through the lens of Dr. Jellinek’s Odor Effects Diagram, oud has a unique profile. Depending on the oud, it may smell like everything in the diagram. The finest ouds constantly change and continuously present a new odor profile.

Oud is exalting because it’s woody (near the stimulating corner of the chart) and, at the same time, erogenic. It is known to have a “Roquefort cheese” note. It is often balsamic (narcotic) and may even have floral notes.

Fine oud offers a seemingly endless complexity of odor and of odor effects. Like very fine wines, it has terroir, a phenomenon described in many ways. I recognize it by a peculiar sense of having smelt the aroma in the distant past, as though in a past life. Images float in front of me. There’s a strange familiarity and sense of place.

Brooklyn Perfume Company’s Oud presents much of the same odor profile, and while I can’t claim to have replicated the complexity of wild oud, Oud is made like a perfume from many years ago, rich in natural materials that often are, like the oud I include, very rare.