There are two main kinds of musk: natural and synthetic. Natural musk comes from a small Himalayan deer which is now endangered. I remember my mother reeking of it, but that was the 1950s. It may be the most delectable smell that exists. In later decades, natural musk was replaced with synthetic musk, sometimes called “white musk.”

Unfortunately, synthetic musk never approaches the aroma of deer musk and, in fact, smells so little like it that I suspect many perfumers have never smelled the real thing. In addition, many people are anosmic to a musk—they just can’t smell it.

When I put together Musk, I used a large combination of musks so that people who are anosmic would be more likely to smell it. While artificial musks are immediately recognizable as such, I have never smelled two the same in my collection of 30 or so.

Much synthetic musk smells like clean laundry or is so very smooth that, again, it reminds me little of mother’s post-party aroma. Here, again, I suspect that those who make these perfumes have neither experienced deer musk or are afraid of offending the public with crude and, sometimes, faecal odours.

I don’t want to offend everybody, but anything that makes a strong statement is likely to offend at least some. So, I put animalistic stuff in the perfume to make it funky and pheromonic. (One friend asked me, bewilderedly, if I were wearing some kind of “attractant.”) The result is something that shimmers between the delicate and the forceful, between clean laundry and animals in heat. It’s not for everyone.

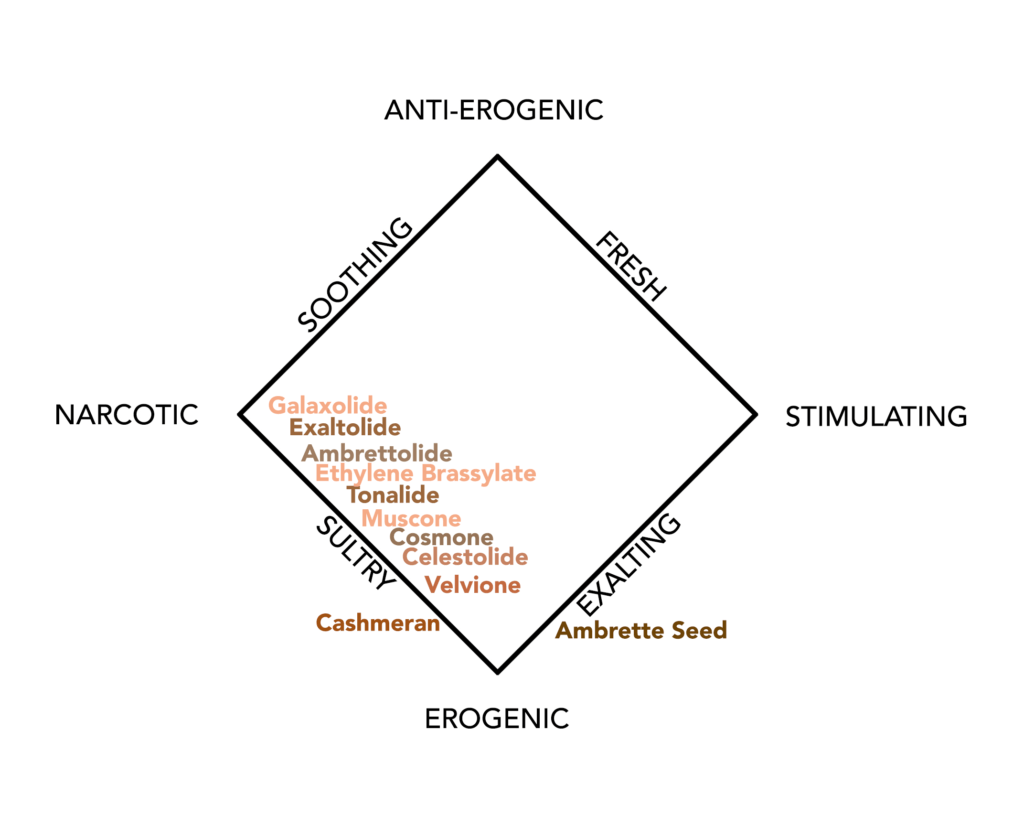

Here, I’ve used Jellinek’s chart as the basis for my own analysis of the perfume and to illustrate how it is structured. It involved a bit of guesswork since each musk has its own aroma profile and I wasn’t able to find information about the odour effects of a specific musk.